What is creativity? This is the fundamental question that resonates in boardrooms, design studios, scientific laboratories, and in the mind of any professional seeking to make a difference. In a world that changes at a dizzying speed, creativity has ceased to be an artist’s luxury to become the most in-demand skill for survival and progress in any sector.

It is no longer enough to have knowledge; the true value lies in applying it in novel ways to solve complex problems, optimize processes, and generate disruptive innovation. Skills like creative thinking are the engine that allows us to go beyond the boundaries of the conventional.

This article will not only answer the question of what creativity is, but it will also provide you with a guide to understand its phases, its types, its relationship with intelligence, and, most importantly, how you can develop and apply it.

The value of creativity

The value of creativity in our society has been recognized by the business sector and academia (Hutten, 2015), and it is frequently seen as a significant competitive advantage. For companies, creativity has proven to be a major contributor to economic and technological development. Furthermore, creativity has been found to be a predictor of educational success and social well-being.

A survey conducted by IBM of more than 1,500 CEOs from 60 countries and 33 industries identified creativity as the most important quality of leadership.

Creative employees conceive ideas, products, services, procedures, and processes that can culminate in innovations that benefit the organization (Lu et al., 2017).

What is creativity? Various definitions

Creativity is the act of turning new ideas into reality, and it is characterized by the ability to perceive the world in a different way. Creativity includes two processes: thinking and then producing.

Creativity is the process of transforming new ideas into a tangible or intangible reality, characterized by the ability to perceive the world from original perspectives. This process involves two fundamental phases: thought (the generation of the idea) and production (its materialization). In this sense, innovation is distinguished as the implementation of these creative solutions to improve people’s quality of life (Ramadani and Gerguri, 2010).

From the field of child development, the LEGO Foundation defines it as “a critical skill and mindset for today’s children,” which is developed through play in an iterative process of connecting, exploring, and transforming the world in new and meaningful ways.

The standard definition of creativity, as highlighted by Runco & Jaeger (2012), consists of two crucial elements: originality and effectiveness. They emphasize that originality is vital, but not sufficient on its own; for an idea to be truly creative, it must also be effective, providing tangible value. This vision has evolved over time; Corazza (2016) points to a transition from the conception of creativity as an elitist phenomenon to a fundamental necessity for all human beings.

The products of creativity are diverse, ranging from tangible objects like works of art and technological devices, to ideas, processes, and innovative systems (Cropley, 2011). However, more recent approaches, such as that of Green et al. (2023), propose focusing the definition on the creative process rather than the final product. Expanding on this perspective, Harvey and Berry (2023) suggest that although novelty and usefulness are pillars of creativity, it can manifest in three interrelated ways: as maximization of one of these attributes, as a balance between them, or as a complete integration of the two.

Manifesto on creativity

A group of 20 academics, led by Vlad Petre Glaveanu (2019), published a manifesto that represents diverse lines of creativity research, marking a conceptual shift within the field:

- Creativity is, at once, a psychological, social, and material phenomenon.

- Creativity is a culturally mediated action.

- Creative action is, at all times, relational.

- Creativity is meaningful.

- Creativity is fundamental to society.

- Creativity is dynamic both in its meaning and its practice.

- Creativity is situated, but its expression shows similarities and differences across situations and domains.

- Creativity needs specification.

- Creativity research needs to consider power dynamics within our analyses and as a field of study.

- The field of creativity studies needs quantitative and qualitative methodologies with a strong theoretical foundation.

- The old literature must be revisited and not abandoned.

- Creativity researchers have a social responsibility.

How does creativity arise?

According to Adams (2005), creativity arises from the confluence of the following three components:

- Knowledge: All the relevant understanding an individual brings to a creative effort.

- Creative thinking: Related to how people approach problems and depends on personality and thinking/working style.

- Motivation: Motivation is generally accepted as the key to creative production, and the most important motivators are intrinsic passion and interest in one’s work.

For his part, Cropley (2011) highlights that the term “creativity” is used in three ways: it refers to a group of processes (creative thinking), a group of personal characteristics of people (creative personality), and to the results (creative product).

Creative thinking

Creative knowledge and advancements have driven human culture worldwide, in diverse areas: sciences, technology, philosophy, arts, and humanities.

Creative thinking is a tangible competence, based on knowledge and practice, that helps people achieve better results, often in constrained and challenging environments. Creative thinking is a necessary competence that people must develop so they can adapt to a continuously changing world.

There is a general consensus that creative thinking can improve a series of other individual skills, including metacognitive abilities, inter- and intrapersonal and problem-solving skills, as well as promote identity development, academic performance, career success, and social engagement.

The Strategic Advisory Board, cited by PISA 2021, defines creative thinking as “the process by which we generate new ideas. It requires specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes. This involves making connections between topics, concepts, disciplines, and methodologies.”

Creative process

The creative process is based on the generation of ideas and their use in the form of innovation, whose analysis and application facilitate problem-solving and the formulation of change strategies.

According to the LEGO Foundation (2019), the creative process includes three linked experiences: Connect, Explore, and Transform, based on the three types of creativity.

- Connect: Being motivated and curious to investigate the world around you.

- Explore: Experimenting, testing, and trying new things.

- Transform: Communicating, reflecting, and sharing ideas with others.

For his part, Dulgheru (2011), in the context of his research, indicates that the sequences of a creative process include:

- Preparation: This is a phase that takes place predominantly at the level of conscious structures and lies in the successive definitions and redefinitions of the problem, as well as in the organized and consistent collection of data that can lead to finding a solution.

- Incubation: The most controversial phase of creation, it takes place predominantly at the level of unconscious structures, where spontaneous and unconscious processing of the problem’s data occurs, as well as of the information that was consciously collected to solve it according to certain criteria.

- Illumination/Inspiration: Represents the moment of becoming aware of a more or less expected relationship between the problem’s data and a specific informational structure, resulting from simultaneous and consecutive conscious and unconscious data processing.

- Evaluation: Consists of consciously examining the ways to balance the problem’s information corpus with the solution’s information corpus in one or more concrete situations.

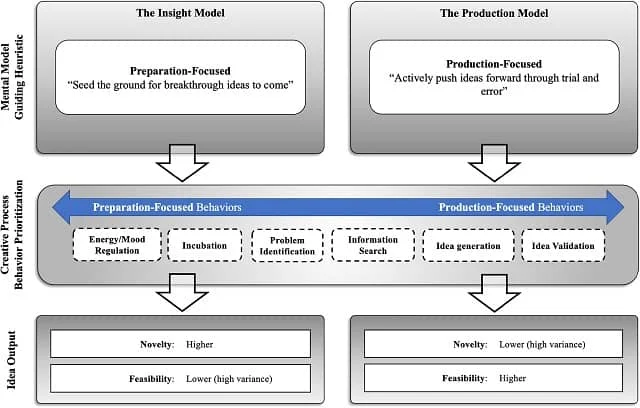

For their part, Lucas and Mai (2022) propose two mental models of the theoretical framework of the creative process: the knowledge model and the production model.

a) Knowledge (insight) mental model

These are derived from the subjective experiences of workers. It leads people to believe that their efforts are more effectively spent on preparing for creative ideas than on producing them. This preparation-focused approach is consistent with research on self-knowledge (i.e., epiphanies), which finds that people believe the likelihood of having an epiphany can be increased through preparatory motivation and attention regulation.

b) Production mental model

Lucas and Mai propose that the subjective experience of analytical ideation promotes the intuition underlying the Production mental model: deliberative ideation is the most effective way to generate creative ideas. In other words, it leads people to focus their efforts on actively ideating and promoting ideas rather than on preparatory behaviors.

Creativity and innovation

Creativity and innovation are related concepts. In this model, according to Nakano and Wechsler (2018), innovation includes two stages: the creative phase (generation of new ideas) and the implementation phase (the application of creative ideas).

In this way, creativity can be defined as the first stage of a problem-solving process, while innovation focuses on the implementation of the idea and its acceptance.

Creativity has been described as the most important determinant of innovation. Thus, creativity can be conceptualized as a necessary precondition for innovation, although the latter depends not only on creativity but also on external factors such as the market and its regulatory forces.

In summary, it can be noted that creativity represents the idea generation process, while innovation is the ability to turn these ideas into something applicable.

Types of creativity

Dietrich (2019) presents a theoretical framework that divides the concept of creativity into three distinct types: a deliberate mode, a spontaneous mode, and a flow mode. On the other hand, Jeff De Graff describes five types of creativity:

- Mimetic: Imitating what exists in nature.

- Bisociative: Connecting rational thoughts with intuitive ones.

- Analogical: Used to alter habitual thinking to make way for new ideas.

- Narrative: The ability to tell stories.

- Intuitive: It is as much about receiving ideas as it is about generating them.

Creativity and intelligence

Sternberg (2003) highlights that there are three main aspects of intelligence that are key to creativity: synthetic, analytical, and practical:

a) Synthetic (creative): the ability to generate ideas that are new, of high quality, and appropriate. An aspect of this ability is to effectively redefine problems. The researcher also highlights that the basis of thinking includes the acquisition of knowledge in three forms:

- Selective encoding: distinguishing relevant from irrelevant information.

- Selective combination: combining relevant information in novel ways.

- Selective comparison: relating new information to old information in novel ways.

b) Analytical: Critical/analytical thinking is involved in creativity as the ability to judge the value of one’s own ideas, to evaluate their strengths and weaknesses, and to suggest ways to improve them.

c) Practical: The ability to apply intellectual skills in everyday contexts and to “sell” creative ideas.

Addressing the new frontiers of creativity

To offer comprehensive coverage, it is vital to explore the most recent debates and applications that the competition often overlooks.

Creativity in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

The emergence of generative Artificial Intelligence has raised fascinating questions. Can a machine be creative? Today, AI is a powerful tool for enhancing human creativity. It can generate drafts, visualize concepts in seconds, and analyze data to find patterns that a human would miss. However, intentionality, consciousness, and deep understanding of context remain human domains. The true revolution lies in human-AI collaboration, where our creativity directs the machine’s computational power.

Ivcevic and Grandinetti (2024) concluded that AI is a promising tool for augmenting human creativity at various levels, especially by improving the average originality and performance of individuals with lower creative ability. For his part, Runco (2023) noted that due to the advancement of artificial intelligence (AI), a revision and update of the standard definition of creativity is required, and highlights that the term “Artificial Creativity” might be the best way to describe the output of AI.

The ethics of creativity and innovation

With every great idea comes great responsibility. Creativity can be used to design sustainable solutions or to create addictive technologies. The ethics of innovation compel us to ask not only if we can create something, but if we should. This involves considering the long-term consequences, social impact, and potential misuse of our creations.

Neuroscience of creativity: What happens in the brain?

Creative thinking has been associated with several brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the default mode network (Tzachrista et al., 2023). Contrary to the “right-brain” myth, modern neuroscience shows that creativity involves the coordinated activation of multiple neural networks throughout the brain. The “Default Mode Network” (active during mental rest and incubation) and the “Executive Control Network” (active during evaluation and focus) work together. Understanding these mechanisms opens the door to optimizing our environments and habits to facilitate these brain processes.

Creativity and mental Well-being

The relationship between creativity and mental health is complex. While there are studied links between certain disorders and high creativity, for most people, the creative act is a powerful tool for well-being. Tobore (2025) concluded that creativity is essential for the meaning of life and for human progress, being the means by which individuals can settle their existential debt.

In this sense, activities such as writing, painting, or creative problem-solving have been shown to reduce stress, improve mood, and provide a sense of purpose and self-expression.

Conclusions

The ability to be creative is a characteristic that is increasingly in demand by different organizations. The good news is that this ability can be developed and can be evaluated.

There are different methods and tools to foster and develop creative abilities in people and to encourage creative thinking; we also offer you a series of recommendations.

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions about Creativity

Is creativity innate or learned?

Both. There is a natural predisposition, but creativity is fundamentally a skill that can be developed and strengthened through practice, learning techniques, and adopting a curious mindset.

How does artistic creativity differ from scientific creativity?

Although the domain is different, the underlying process is similar. Both seek patterns, connect seemingly unrelated ideas, and generate something new. The main difference lies in the objective and the validation criteria: beauty and emotion in art; truth and replicability in science.

How can I be more creative in my work?

Question existing processes by asking “what if…?”. Collaborate with colleagues from other departments to get new perspectives. Dedicate time to think without interruptions and don’t be afraid to propose ideas that seem unconventional at first. Apply the “Jobs to be Done” methodology to understand the real problem you are trying to solve.

References

Adams, K. 2005. The Source of Innovation and Creativity. A Paper Commissioned by the National Center on Education and the Economy for the New Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce. 59 p.

Corazza, G. (2016) Potential Originality and Effectiveness: The Dynamic Definition of Creativity, Creativity Research Journal, 28:3, 258-267, DOI: 10.1080/10400419.2016.1195627

Cropley, A. J. (2011). Definitions of creativity. In M. A. Runco & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (pp. 511-524). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

De Graff J. 2013. Descubre los cinco tipos de creatividad. Expansión.

Dietrich, A. Types of creativity. Psychon Bull Rev 26, 1–12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-018-1517-7

Dulgheru, Valeriu. (2011). Types and forms of creativity. Meridian Ingineresc, ISSN 1683-853X. -. pp. 97-98.

Garcés S. 2018. Creativity in science domains: a reflection. Atenea 517, pp. 247-253.

Green, A. E., Beaty, R. E., Kenett, Y. N., & Kaufman, J. C. (2023). The Process Definition of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 36(3), 544–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2023.2254573

Harvey, S., & Berry, J. W. (2023). Toward a meta-theory of creativity forms: How novelty and usefulness shape creativity. Academy of Management Review, 48(3), 504-529. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2020.0110

Hutten, E. (2015). The concept of creativity : the relationship between usefulness and creativity.

Ivcevic, Z., & Grandinetti, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence as a tool for creativity. Journal of Creativity, 34(2), 100079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjoc.2024.100079

Lu J., Modupe Akinola, Malia F. Mason. 2017. ‘‘Switching On” creativity: Task switching can increase creativity by reducing cognitive fixation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 139: 63-75

Lucas Brian J., Mai Ke Michael. 2022. Illumination and elbow grease: A theory of how mental models of the creative process influence creativity, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Volume 168, 104107, ISSN 0749-5978, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2021.104107.

Nakano, T. C., & Wechsler, S. M. (2018). Creativity and innovation: Skills for the 21st Century. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 35(3), 237-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752018000300002

OECD. 2019. PISA 2021 – Creative Thinking Framework (Third Draft). 56 p.

Ramadani, Veland & Gerguri, Shqipe. (2010). Innovation: Principles and Strategies. University Library of Munich, Germany, MPRA Paper.

Runco, Mark & Jaeger, Garrett. (2012). The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal – CREATIVITY RES J. 24. 92-96. 10.1080/10400419.2012.650092.

Runco, M. A. (2023). Updating the Standard Definition of Creativity to Account for the Artificial Creativity of AI. Creativity Research Journal, 37(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2023.2257977

SUDOE – FEDER. Crea Business Idea: Manual de la Creatividad Empresarial. 52 p.

Sternberg, R. 2003. Creative thinking in the Classroom. Scandinavian Journal of Education Research; Vol. 47, No 3.

Tobore, T. O. (2025). On creativity and meaning: The intricate relationship between creativity and meaning in life and creativity as the means to repay existential debt. Communicative & Integrative Biology, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/19420889.2025.2484526

Tzachrista, M., Gkintoni, E., & Halkiopoulos, C. (2023). Neurocognitive Profile of Creativity in Improving Academic Performance—A Scoping Review. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111127

Vlad Petre Glaveanu, et al. 2019. Advancing Creativity Theory and Research: A Socio-cultural Manifesto. Journal of Creative Behavior, Volume54, Issue3, September 2020, Pages 741-745 https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.395

Editor and founder of “Innovar o Morir” (‘Innovate or Die’). Milthon holds a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation (UPV) and Market-Oriented Innovation Management (UPCH-Universitat Leipzig). He has practical experience in innovation management, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA) and worked as a consultant on open innovation diagnostics and technology watch. He firmly believes in the power of innovation and creativity as drivers of change and development.