In the complex web of modern politics, the global economy, and social challenges, organizations dedicated to research, analysis, and proposing solutions emerge: think tanks. These “idea laboratories” or “centers of thought” have become influential actors, often operating behind the scenes, but with a tangible impact on the decisions that shape our world. But, what exactly is a think tank? And how does this key piece of the sociopolitical machinery work?

This article delves into the universe of think tanks, exploring their definition, history, functions, funding, credibility, and prominent examples. We will analyze what think tanks do, how think tanks are funded, and address the crucial question: are think tanks credible?

What is a Think Tank?

To understand the phenomenon, let’s start with the basics, let’s answer the question: What is a think tank?

Although there is a lack of consensus on what exactly constitutes a think tank, what they do, and whether they truly manage to effectively shape political ideas (Ruser, 2018); the term think tank (whose closest Spanish translation would be “laboratorio de ideas” or “centro de pensamiento”) refers to an organization, institute, corporation, or group that conducts research and promotes debate on issues of public relevance, such as social policies, political strategies, economics, military affairs, technology, and culture.

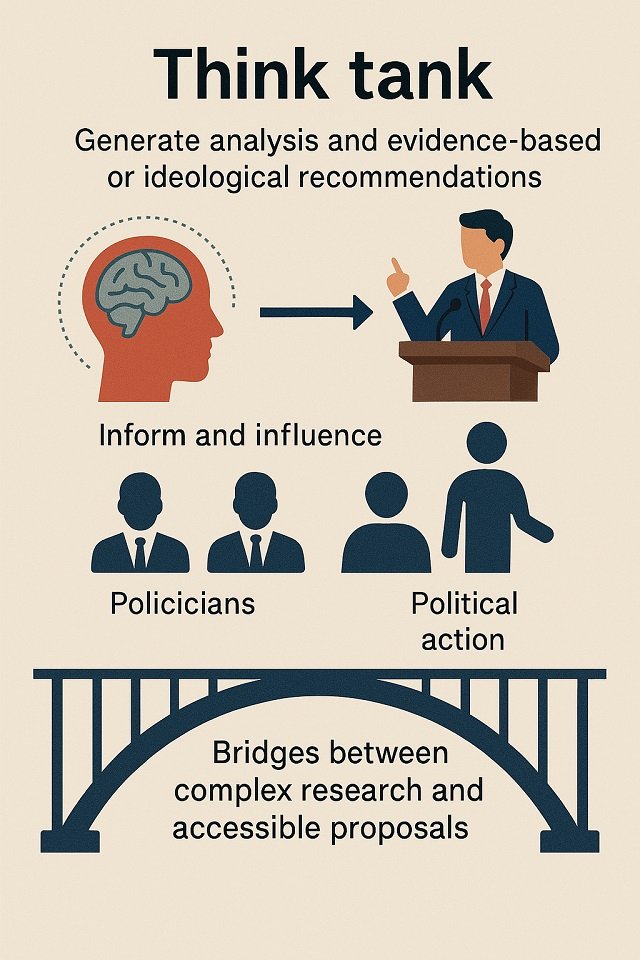

The meaning of think tank centers on its primary function: generating in-depth analysis and evidence-based recommendations (or based on a particular ideological perspective) with the aim of informing and often influencing decision-makers (politicians, officials, business leaders) and public opinion. Think tanks are ‘bridges’ between academic knowledge and political action; in other words, they try to translate complex research into concrete and accessible proposals.

Think tanks, therefore, are entities dedicated to thinking, analyzing, and proposing. Unlike universities, whose main focus is usually fundamental research and teaching, think tanks are fundamentally oriented towards public policy. They do not necessarily seek knowledge for its own sake, but rather knowledge applied to specific societal problems.

Neither are they exactly pressure groups (lobbies), although the line can sometimes be blurry. While a lobby seeks to directly influence legislation in favor of specific interests (often corporate or sectoral), a think tank theoretically bases its influence on the quality and relevance of its research and analysis. However, many think tanks carry out advocacy activities to disseminate their ideas and recommendations, bringing them closer to the sphere of direct political influence.

In summary, a think tank is a research and analysis center, often independent (although its degree of independence is a crucial issue we will address), focused on generating ideas and proposals to tackle public problems and guide policy. Its real significance lies in its ability to shape debates and offer roadmaps to decision-makers.

Origins and History: The Rise of Political ‘Brains’

Although the term “think tank” was popularized during World War II to refer to safe spaces where military strategies were discussed (Xifra, 2005), the precursor organizations date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Fabian Society (1884) in the United Kingdom, dedicated to promoting gradual socialism, and the Brookings Institution (1916) in the United States, focused on public policy analysis from an initially more neutral perspective, are early examples.

The real boom of think tanks occurred after World War II, especially in the United States. The growing complexity of government problems, the Cold War, and the need for specialized expertise spurred the creation of entities like the RAND Corporation (Research and Development), initially focused on military analysis for the U.S. Air Force, but which later broadened its scope.

The 1970s and 1980s marked another stage of significant expansion, coinciding with greater ideological polarization. Think tanks emerged with more markedly conservative (like The Heritage Foundation, 1973) or liberal/progressive agendas, seeking to actively influence political debate and the administrations of the time. This period consolidated the image of the think tank not only as an analysis center but also as an ideological actor.

Globalization and the end of the Cold War opened new areas of focus (global economy, environment, human rights), and think tanks multiplied not only in North America and Europe but worldwide, including Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Initiatives like the Think Tank Initiative (TTI), launched by several foundations in 2008, sought to strengthen the capacity of think tanks in developing countries so they could contribute more effectively to public policy debates in their respective contexts.

Today, think tanks form a diverse and global ecosystem, adapting to the digital age and facing new challenges in an increasingly complex and interconnected world. Understanding what these centers of thought are involves recognizing this historical evolution and their growing relevance in the global political landscape.

Types of Think Tanks

Not all think tanks are the same. Different types of think tanks exist; academic think tanks tend to focus on rigorous research and influencing “elite opinion,” while advocacy think tanks combine an ideological or partisan stance with “aggressive marketing” to influence current political debates (Ruser, 2018). However, all types of centers of thought seek to project an image of scientific authority.

Think tanks can be classified according to various criteria, which helps to understand the variety and complexity of this universe.

By Ideological Orientation

- Conservative/Libertarian: Tend to promote free-market policies, reduction of public spending, traditional values (e.g., The Heritage Foundation, Cato Institute in the U.S.; FAES in Spain).

- Liberal/Progressive: Advocate for state intervention in the economy, social welfare policies, environmental protection (e.g., Center for American Progress, Brookings Institution – although often considered more centrist -, in the U.S.; Fundación Alternativas in Spain).

- Centrist/Moderate: Seek balanced positions or pragmatic solutions that transcend traditional ideological divisions.

- Non-Partisan/Independent: Strive to maintain ideological neutrality, focusing on analysis based on data and evidence, although total objectivity is a difficult ideal to achieve (e.g., RAND Corporation, Pew Research Center).

By Area of Focus

- Generalist: Cover a broad spectrum of public policies (economic, social, international, etc.).

- Specialized: Concentrate on a specific area such as foreign policy (e.g., Council on Foreign Relations – CFR, Chatham House), economics (e.g., Bruegel in Europe), environment (e.g., World Resources Institute), security and defense (e.g., International Institute for Strategic Studies – IISS), social development, etc.

By Structure and Affiliation

- Independent: Are autonomous organizations, generally non-profit, although their funding may come from various sources.

- University-Affiliated: Maintain formal ties with academic institutions, benefiting from their resources and reputation, but maintaining some operational autonomy.

- Party-Affiliated: Function as intellectual arms of parties, developing ideas and programs for them (e.g., German political foundations like Konrad Adenauer Stiftung -CDU- or Friedrich Ebert Stiftung -SPD-). Vande Walle and de Lange (2025) identified four types of political party think tanks: Party Supporters, Party Supporters, Party Promoters, and Party Intellectuals.

- Governmental or Quasi-Governmental: Funded wholly or partially by the government, often to conduct specific analyses for state agencies.

- Corporate: Created or funded by companies or industry sectors to research topics of interest to them.

By Geographical Scope

- National: Focused on the policies of a specific country.

- Regional: Centered on a geographical region (e.g., European Union, Latin America).

- Global: Address issues of international scope and have a presence or influence in multiple countries.

Understanding this diversity is fundamental to evaluating what think tanks do and what their possible bias or perspective is. A think tank funded by the energy industry will likely approach climate change differently than one funded by environmental foundations.

What Do Think Tanks Do?

Beyond the definition, it is crucial to understand the concrete activities these organizations carry out. Think tank research possesses characteristics of spatio-temporal domain, meaning it must review the past, understand the present, and foresee the future (Jiaofeng, 2020); in this sense, the activities of centers of thought encompass a range of interconnected functions:

Research and Analysis

This is the central activity. Think tanks employ experts (academics, former officials, analysts) to investigate complex problems, collect and analyze data, and generate knowledge on specific topics. This research can be long-term and academic, or rapid and oriented towards responding to current events. The quality and rigor of this research are key to their credibility.

Tarango and Delgado (2024) highlight that Think Tanks, especially Latin American TT-FIs [Think Tanks focusing on International Finance/Foreign Investment – assuming this interpretation of FI], are important for their role in generating specialized knowledge, forming intellectual elites, their potential influence on public opinion and public policies, and their function as connectors between academia, government, and civil society.

Public Policy Development

Based on their research, think tanks formulate concrete policy recommendations. They propose solutions to social, economic, or political problems, design programs, suggest legislative reforms, or evaluate existing policies. The goal is to offer “roadmaps” to decision-makers.

Dissemination and Communication

Generating ideas is not enough; they must be made known. Think tanks publish reports, studies, white papers (policy papers), opinion articles, blogs, and content for social media. They organize conferences, seminars, round tables, and press conferences to present their findings and foster debate. They actively seek media attention to amplify their message. The European Parliament’s website (Europarl Think Tank) is an example of a platform that aggregates and disseminates this type of analysis at the European level.

Convening and Networking

They act as convergence centers, bringing together experts, politicians, officials, business leaders, academics, and civil society representatives to discuss key issues. They facilitate dialogue and network creation among relevant actors, often serving as “neutral ground” for debate.

Education and Training

Some think tanks offer training programs, scholarships, or courses for young professionals, students, or public officials, helping to train future generations of leaders and analysts.

Direct Advising

In many cases, think tank experts directly advise governments, political parties, or international institutions, testify before parliamentary committees, or participate in expert commissions.

Advocacy

Although distinct from direct lobbying, many think tanks, especially ideologically oriented ones, actively promote their policy proposals, seeking to persuade decision-makers and the public of the validity of their approaches.

How Are Think Tanks Funded?

The issue of funding is crucial, as it can influence the independence, research agenda, and public perception of a think tank. The sources are varied:

Foundation Donations

Many philanthropic foundations (like the Ford Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Open Society Foundations, or conservative foundations linked to the Koch brothers) are major funders of think tanks, often supporting specific projects or research areas aligned with their own objectives.

Corporate Donations

Some companies finance think tanks, either through general donations or by supporting research on topics affecting their sector (energy, finance, technology, etc.). This funding source is often scrutinized for potential conflicts of interest.

Individual Donations

Contributions from private individuals, sometimes large donors with ideological affinities or specific interests, are also a significant source for many think tanks.

Government Contracts and Grants

Some think tanks conduct research on commission for national or international government agencies. This can provide stable income but also raises questions about independence from the contracting government.

For example, Zhang (2021) concluded that think tanks in China are mainly funded by government funds and therefore primarily cater to the current policies of the Chinese government.

Endowments

Some older, more established think tanks have their own capital (endowment) whose returns help fund their operations, granting them greater financial stability and independence.

Publication and Event Sales

Although generally a minor source, sales of books, reports, or charging admission fees for conferences can generate some income.

Membership Fees

Some models include membership programs for individuals or companies.

The funding structure varies enormously among think tanks. Some rely heavily on a small number of large donors or government contracts, while others have a more diversified funding base. Transparency about funding sources is a key indicator for assessing potential external influence on a think tank’s agenda and results.

Are Think Tanks Credible?

This is perhaps one of the most complex and debated questions. Are think tanks credible? The answer is not a simple yes or no. The credibility of a center of thought [or think tank] depends on multiple factors and must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Xifra (2005) states that centers of thought are evolving from the traditional model of the independent think tank towards the figure of the “advocacy tank,” which operates transparently to defend the interests of its members and benefactors.

Factors Contributing to Credibility

- Transparency: Openness about their funding sources, research methodology, data used, and potential conflicts of interest is fundamental. Think tanks that hide their donors or do not explain how they reached their conclusions tend to generate distrust.

- Quality and Rigor of Research: The use of solid methodologies, verifiable data, objective analysis, and, in some cases, peer review of their publications, reinforces credibility.

- Independence: The ability to set their own research agenda and publish findings without interference from their funders or political interests is crucial. Diversified funding can contribute to this independence.

- Reputation and Track Record: Think tanks with a long history of producing high-quality analysis and with recognized experts in their fields tend to enjoy greater credibility.

- Plurality of Perspectives: Although many think tanks have an ideological orientation, those that acknowledge the complexity of problems, present different points of view, or include critical analyses of their own positions may be perceived as more credible.

Factors That Can Undermine Credibility

- Lack of Transparency: Secrecy about funding or methodology generates suspicion of hidden biases or covert agendas.

- Extreme Ideological Bias or Partisanship: When a think tank seems to function primarily as an echo of an ideology or political party, sacrificing analytical rigor for the defense of a predetermined stance, its credibility as an objective source of analysis suffers. In this regard, Troy (2012) reports the case of think tanks in Washington, which have undergone a significant transformation over the last half-century, shifting from relatively non-partisan research centers dedicated to policy development to increasingly politicized institutions oriented towards defending partisan interests.

- Undue Influence of Funders: If there is evidence that donors (be they corporations, governments, or individuals) dictate the conclusions of the research, credibility “evaporates.”

- Low-Quality Research: The use of erroneous data, flawed methodologies, or superficial analysis damages reputation.

- Conflict of Interest: If the think tank’s experts have personal or financial interests in the policies they recommend, their objectivity can be questioned.

Think tank reviews and rankings, such as the University of Pennsylvania’s “Global Go To Think Tank Index Report” (although also subject to methodological debate and which has not been updated since 2020), attempt to evaluate and compare think tanks worldwide, but the best approach is critical analysis by the information consumer (journalists, academics, citizens, politicians). It is essential to ask: Who funds this think tank? What is its methodology? Does it present solid evidence? Does it acknowledge alternative points of view? Does it have a clear agenda?

In conclusion, while many think tanks perform valuable work and contribute rigorous analysis to public debate, it is essential to approach them with a critical spirit, aware of their possible biases and the influence their funding sources and ideological orientations may exert. Credibility is not inherent to the term think tank; it is earned and maintained through transparency and rigor.

Examples of Think Tanks Worldwide

The global growth of think tanks responds to a growing demand for scientific knowledge in increasingly complex societies (Ruser, 2018). To illustrate the diversity and scope of these organizations, here are some prominent examples at the global and regional level:

Global and U.S. Examples

- Brookings Institution (USA): One of the oldest and most cited. Generally considered center or center-left, covers a wide range of public policies.

- The Heritage Foundation (USA): Influential conservative think tank, with a strong impact on Republican politics.

- Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) (USA): Highly influential in U.S. foreign policy, publishes the journal Foreign Affairs. Mostly considered centrist and pragmatic.

- RAND Corporation (USA): Military origins, now covers a vast range of topics with an analytical and data-driven approach. Often works under government contract.

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Global): Focused on international relations, with centers in Washington, Moscow, Beirut, Beijing, Brussels, and New Delhi.

- Cato Institute (USA): Prominent libertarian think tank, advocates for free markets and limited government.

- Pew Research Center (USA): Known for its demographic research, public opinion polls, and analysis of social trends, with a strong emphasis on neutrality and data.

European Examples:

- Chatham House (UK): One of the most prestigious international relations think tanks in the world (Royal Institute of International Affairs).

- Bruegel (Belgium): Focused on European economic policy, with a reputation for independence and rigorous analysis.

- Centre for European Reform (CER) (UK/EU): Works on issues related to the European Union, with a pro-European perspective.

- German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) (HQ in USA, strong presence in Europe): Fosters transatlantic cooperation.

- German Political Foundations (Konrad Adenauer, Friedrich Ebert, etc.): Linked to parties, but with significant international operations in analysis and cooperation.

- Real Instituto Elcano (Spain): Main Spanish think tank in international and strategic studies.

- CIDOB (Barcelona Centre for International Affairs) (Spain): Another reference point in international analysis from Barcelona.

- FAES (Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales) (Spain): Linked to the Partido Popular, conservative orientation.

- Fundación Alternativas (Spain): Progressive think tank, close to the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party.

Examples in Latin America:

- Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV) (Brazil): Highly prestigious academic institution that also functions as an influential think tank in economics and public policy.

- CIPPEC (Centro de Implementación de Políticas Públicas para la Equidad y el Crecimiento) (Argentina): [Center for the Implementation of Public Policies for Equity and Growth] One of Latin America’s most recognized think tanks, focused on public policies for development.

- Fedesarrollo (Colombia): Economic and social research center of great influence in Colombia.

These think tank examples barely scratch the surface, but they illustrate the ideological, thematic, and geographical variety of these organizations. Each has its own history, funding structure, focus, and level of influence.

Global Impact and Scope: Think Tanks on the World Stage

Think tanks do not operate in a vacuum. Their ultimate goal is to have an impact, influence policy, public debate, and the decisions of key actors. Their influence manifests in various ways:

- Agenda Setting: They can introduce new topics into public debate or reframe existing problems, drawing the attention of politicians and the media.

- Provision of Expertise: They offer specialized analysis that governments and international organizations may lack the internal capacity to generate.

- Policy Formulation: Their proposals and recommendations often find resonance in government programs, laws, or political strategies. Chen et al. (2023) report that the experience of transforming Chinese universities into think tanks has involved strong government support and the creation of incentives for social science researchers to produce policy-relevant research reports.

- Legitimization of Ideas: They can lend a veneer of intellectual rigor and credibility to certain ideological or political stances.

- Elite Training: They serve as a talent pool, with experts often moving into government positions (the so-called “revolving door”) and vice versa.

- Track II Diplomacy: They facilitate informal dialogue between actors from conflicting countries or those with strained relations, in a less formal setting than official diplomacy.

Globally, think tanks play a role in shaping global governance, international trade, security policies, and development cooperation. Organizations like the World Economic Forum (although not strictly a traditional think tank, it shares convening and debate functions) or conferences organized by major international think tanks bring together world leaders to discuss global challenges.

The aforementioned Think Tank Initiative (TTI) is an example of the recognition of the importance of these institutions in the Global South. By supporting think tanks in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the TTI sought to strengthen their capacity to produce locally relevant research and participate effectively in policymaking processes in their countries, contributing to a more balanced global knowledge ecosystem.

However, global influence also poses challenges. The concentration of influential think tanks in the Global North can perpetuate certain perspectives and agendas. Furthermore, competition for funding and attention can lead to a “commodification of ideas,” where think tanks focus on “marketable” topics instead of long-term structural problems.

The Future of Think Tanks: Challenges and Opportunities

The landscape in which think tanks operate is constantly changing. They face both significant challenges and new opportunities:

Challenges

- Crisis of Confidence and Polarization: In an environment of growing distrust towards elites and institutions, and high political polarization, think tanks (especially those perceived as ideological) struggle to maintain their credibility and relevance as objective sources. In this regard, Troy (2012) states that more political think tanks could hinder policymakers’ task by not offering the rigorous and innovative research needed to address today’s complex challenges.

- Competition in the Marketplace of Ideas: The proliferation of online information (and disinformation) sources, blogs, social media, and alternative media outlets creates a noisier and more competitive environment for capturing attention. In this regard, Li et al. (2023) conclude that a growing focus on talent in knowledge service ecosystems can lead to the establishment of innovative expert groups in many countries and aid the creation of centers of thought.

- Funding Pressures: Dependence on donors can create pressure on the research agenda. The search for stable funding remains a constant challenge, especially for smaller think tanks or those in regions with less philanthropic tradition.

- Adaptation to the Digital Age: They need to master new communication tools, data visualization, and Big Data analysis to remain relevant and effective.

- Transparency and Accountability: Public demand for greater transparency about who funds think tanks and how they operate continues to grow.

Opportunities

- Growing Complexity: Global problems (climate change, pandemics, artificial intelligence, geopolitical tensions) are increasingly complex and require expert analysis, reinforcing the need for think tanks.

- New Technologies: Digital tools offer new ways to research, analyze data, communicate findings, and reach broader audiences. Artificial intelligence can enhance analytical capabilities.

- Global Collaboration: The need to address transnational problems encourages collaboration among think tanks from different regions.

- Focus on Implementation: There is a growing demand not only for ideas but also for analysis on how to implement policies effectively. Li (2015) proposes the concept of “think tank 2.0” (TT2.0), designed to host deliberative analysts and integrate policy research with public participation, deliberation, and dispute resolution.

- Greater Citizen Participation: Think tanks can play a role in translating complex debates and fostering more informed citizen participation.

The future of think tanks will depend on their ability to adapt to this changing environment, maintaining intellectual rigor and transparency, while finding innovative ways to communicate and demonstrate their value in society.

Conclusion

Think tanks, those “idea laboratories” or “centers of thought,” are complex and multifaceted actors in the contemporary political, economic, and social landscape. From their fundamental definition to their daily operations and funding, we have explored the diverse dimensions of these influential organizations.

It is important to highlight that think tanks are not a panacea, but they can be useful agents of social change and add value in the current context by producing research whose quality goes beyond traditional academic measures of rigor (Hurst, 2020); in this sense, the meaning of a think tank goes beyond simple research; it involves analysis, proposal, dissemination, and influence on policy. Their history shows an evolution from technical analysis centers to key ideological actors. The diversity of examples globally and regionally reflects a wide range of approaches, specializations, and orientations.

The question of credibility remains central. Transparency, methodological rigor, and independence are crucial, but often difficult to evaluate objectively. It is the responsibility of everyone (citizens, journalists, academics, politicians) to approach the output of think tanks with a critical spirit, always considering their possible agenda and funding sources. Understanding what a think tank is and its real meaning implies recognizing both its potential contribution of expert knowledge and its possible role as defenders of particular interests.

In a world facing increasingly complex challenges, the need for deep analysis and well-founded solutions is undeniable. Think tanks are positioned to play a vital role in this context, but their legitimacy and effectiveness will depend on their commitment to intellectual integrity and openness. They are, and likely will remain, fundamental pieces in the intricate game of ideas that shapes our collective future.

References

Chen, K., Wupur, A., Abudouguli, A., & Yang, G. (2023). Measuring the knowledge transfer efficiency of social science in Chinese universities from a think tank perspective. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 90, 101745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2023.101745

Geng, Q., Chuai, Z., & Jin, J. (2022). Webpage retrieval based on query by example for think tank construction. Information Processing & Management, 59(1), 102767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102767

Hurst, A. W. (2020). Reflections from the Think Tank Initiative and their relevance for Canada. Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement, 42(3), 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2020.1820313

Jiaofeng, PAN (2020) “Double Helix Structure of Think Tank Research,” Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Chinese Version): Vol. 35 : Iss. 7 , Article 12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20200706002

Li, Y. Think tank 2.0 for deliberative policy analysis. Policy Sci 48, 25–50 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-014-9207-4

Li, Y., Shen, J., & Cetindamar, D. (2023). Think Tank Innovation-Driven Knowledge Service Ecosystems: A Conceptual Framework and Case Study Application. Sustainability, 15(10), 8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108355

Ruser, A. (2018). What to think about think tanks: Towards a conceptual framework of strategic think tank behaviour. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 31, 179-192.

Tarango, J., & Delgado, R.-M. (2024). Ecosistema de información en el modelo Think Tank Formativo-Investigativo en Latinoamérica: un análisis sobre el consumo de información y la generación de conocimiento. Scire: Representación Y organización Del Conocimiento, 30(2), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.54886/scire.v30i2.5027

Troy, T. (2012). Devaluing the think tank. National Affairs, 10(Winter), 75-90.

Vande Walle, B., & de Lange, S. L. (2025). Understanding the Political Party Think Tank Landscape: A Categorization of Their Functions and Audiences. Government and Opposition, 60(1), 104–124. doi:10.1017/gov.2024.5

Xifra, J. (2005). Los think tank y advocacy tank como actores de la comunicación política. Anàlisi: quaderns de comunicació i cultura, (32), 073-91.

Zhang, D. (2021). The media and think tanks in China: The construction and propagation of a think tank. Media Asia, 48(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/01296612.2021.1899785

Editor and founder of “Innovar o Morir” (‘Innovate or Die’). Milthon holds a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation (UPV) and Market-Oriented Innovation Management (UPCH-Universitat Leipzig). He has practical experience in innovation management, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA) and worked as a consultant on open innovation diagnostics and technology watch. He firmly believes in the power of innovation and creativity as drivers of change and development.