In a world grappling with the consequences of a linear economy, where resources are extracted, used, and discarded, the concept of a circular economy emerges as a beacon of hope. At the heart of this transformative approach lies the circular business model, a paradigm that redefines how companies operate, creating value not just for themselves but for the entire ecosystem.

Circular business models are important for implementing the concept of a circular economy at the organizational level (Geissdoerfer et al., 2020) and helping companies transition towards a circular economy by adopting strategies such as reuse, repair, and remanufacture (Nußholz, 2017), aiming to contribute to environmental and social sustainability goals in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Awan and Sroufe, 2022).

What are Circular Business Models?

The circular economy moves away from the traditional linear model, where resources are finite, and waste is inevitable. Instead, it envisions a closed loop where resources continuously circulate through production, consumption, and recovery, minimizing waste and maximizing value.

Nußholz (2017) defines circular business models (CBM) as: “the way a company creates, captures, and delivers value with a value creation logic designed to improve resource efficiency by extending the lifespan of products and components and closing material loops.”

Meanwhile, Salvador et al. (2020) emphasize that: “Circular Business Models are business models that enable systems that are regenerative by nature; they seek to maintain the value of resources at their highest possible level for as long as possible and to eliminate or reduce resource leakage by closing, slowing, or narrowing resource loops.”

In summary, circular business models are based on a circular logic that seeks to maximize resource efficiency, extend the life of products and components, and close material loops. In this way, companies not only capture and deliver value to their customers but also contribute to a regenerative system that minimizes resource leakage and reduces their environmental impact.

Principles and Characteristics of Circular Business Models

Circular business models facilitate the implementation of the circular economy (CE) and incorporate a set of guiding principles that drive their success:

- Design for Longevity: Products are designed to provide durability, repairability, and reusability, extending their lifespan.

- Eliminate Waste: Waste generation is minimized through efficient design, manufacturing processes, and material choices.

- Materials in Circulation: Materials are kept in use for as long as possible through reuse, remanufacturing, and recycling.

- Regenerate Natural Systems: Companies actively support the restoration and preservation of natural ecosystems.

Benefits of Circular Business Models

The adoption of circular business models offers numerous benefits that go far beyond environmental advantages:

- Improved Resource Security: Companies reduce their dependence on finite resources, ensuring a stable supply chain.

- Reduced Environmental Impact: Waste generation and pollution are minimized, protecting the environment.

- Increased Profitability: Resource efficiency and waste reduction generate cost savings and better margins. Chkareuli et al. (2024) reported that under identical capital investment conditions for the production and commercialization of wine, the circular business model outperforms the linear model in terms of profitability.

- Enhanced Brand Reputation: Consumers value companies committed to sustainability, boosting brand image. Mostaghel and Chirumalla (2021) and Lopes et al. (2023) highlight that purchase intentions and customer behavior are crucial factors for the successful implementation of circular business models.

- Opportunities for Innovation and Growth: Circularity fosters innovation in product design, processes, and business models.

Risks of Implementing Circular Business Models

Tuni et al. (2024) studied how manufacturers view the risks of switching to circular business models and concluded the following:

- Market and Supply Chain Concerns: Manufacturers from various industries shared similar concerns about customer acceptance of new CBM products and the stability of the economy. There were also concerns about the ability to efficiently recover used products (reverse logistics).

- Risks Vary by CBM Type: Different circular business model strategies carry unique risks. For example, extending product lifespan raised concerns about changes in government regulations. On the other hand, using recycled materials (circular supplies) raised concerns about the technical feasibility, availability, and quality of those materials.

- More Risks with Less Control: Manufacturers with less control over their supply chains (less vertically integrated) faced greater risks. Dependence on external partners for material and product recovery activities magnified existing concerns.

Types of Circular Business Models

Geissdoerfer et al. (2023), based on their research, report three main approaches that companies take towards CBMs:

- Circular Startups: New businesses built entirely around a circular business model.

- Diversification: Existing companies that add a circular business model as a new offering.

- Transformation: Existing companies fundamentally changing their core business model to be more circular.

Additionally, the circular economy encompasses a wide range of business models, each tailored to specific contexts and resource flows:

- Circular Inputs: Adoption of renewable resources. Companies transition to renewable and sustainable raw material sources, reducing their environmental footprint.

- Product as a Service: Redefining ownership and consumption. Products are offered as a service, shifting the focus from ownership to access and extending product lifespan.

- Product Life Extension: Extending product value. Companies implement strategies to prolong product life through repairs, refurbishments, and upgrades.

- Resource Recovery: Turning waste into resources. Waste materials are recovered and reintegrated into the production process, creating new value streams. Vegter et al. (2020) highlight that the supply chain in a circular business model consists of two additional processes compared to a supply chain in a linear business model: Use and Recovery.

- Collaborative Economy: Collaboration for sustainable consumption. Platforms facilitate the sharing and reuse of products and services, reducing individual ownership and consumption.

Circular Flow Model: Visualizing the Cyclical Nature of Circularity

Stages of the Circular Flow Model

The circular flow model describes the interconnected stages of a circular economy:

- Production: Products are manufactured using renewable inputs and sustainable practices.

- Consumption: Consumers use products, extending their lifespan through repair and maintenance.

- End of Use: Products are returned to the system for reuse, remanufacture, or recycling.

- Recovery: Materials are extracted from products at the end of their life cycle and reintroduced into the production cycle.

Implementing the Circular Flow Model in Practice

Companies can implement the circular flow model by:

- Design for Disassembly: Products are designed to facilitate disassembly and material separation.

- Establishing Return Systems: Consumers are incentivized to return products for recovery.

- Partnering with Recyclers and Remanufacturers: Collaborate with experts to ensure efficient material recovery.

- Investing in Circular Technologies: Adopt innovative technologies that support circular processes.

Roadmap to the Circular Business Model

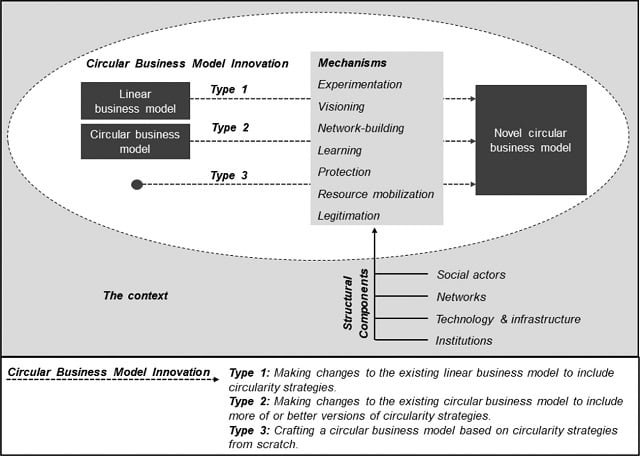

It is important to note that the support of a company’s top management is key to implementing a circular business model from the core of the company outward (Salvador et al., 2020). Additionally, Susur and Engwall (2022) propose a conceptual framework to illustrate how circular business models emerge through innovation mechanisms within transitions to a circular economy. They suggest that “social actors,” “networks,” “technology and infrastructure,” and “institutions” are four structural contextual components of these transitions.

Brändström et al. (2024) found that companies in different sectors experience different primary barriers when implementing a circular business model. Geissdoerfer et al. (2023) studied the factors influencing companies to adopt circular business models and report that business growth, cost reduction, and customer demand are key drivers for startups and diversification. In contrast, traditional companies transforming their models focus more on sustainability goals and long-term resilience.

In the case of agri-food systems, De Bernardi et al. (2023) identified seven critical issues for the transition to circular food systems: consumer behavior, multi-stakeholder coordination, business models, digital technologies, barriers, transition processes, and measurement and performance systems.

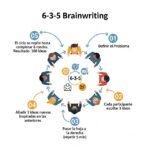

On the other hand, Baldassarre et al. (2024) recommend the following lessons for managers to overcome barriers in their process towards a circular business model:

- Iteratively detailing the dimensions of a circular business model helps identify implementation barriers with more specificity and accuracy.

- Understanding the chain reactions of barriers in the business model dimensions is functional to address the root causes behind implementation failures.

- To overcome cultural barriers, it is important to involve a matchmaker who leads the circular business modeling process without direct economic interests.

- Engaging policymakers in the debate on economic barriers to circular value capture is essential for achieving implementation.

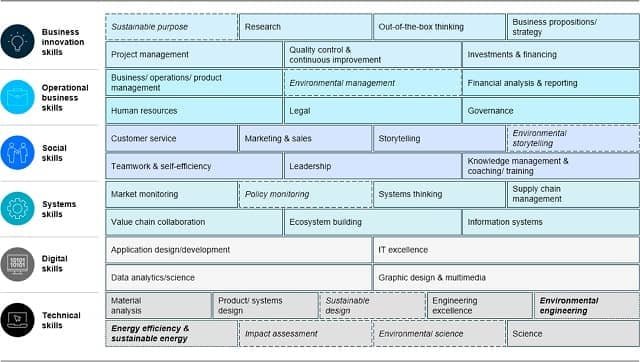

Evaluation of Current Operations and Identification of Circular Opportunities

Companies conduct a comprehensive evaluation of their operations to identify areas for circularity. They should also consider the capabilities of their personnel regarding circular economy topics. Straub et al. (2023) published a skills taxonomy that can be used for activities such as competency mapping, targeted recruitment, upskilling and reskilling, and performance management.

Development of a Circular Business Model Strategy

A strategic plan is developed that outlines the specific objectives of the circular business model and the implementation measures. This strategic plan should include the development of staff capabilities in circular economy concepts and the technologies that can be used.

Implementation of Circular Practices and Progress Measurement

Circular practices are integrated into operations, and progress is monitored through key performance indicators. Monitoring progress is important to reduce the risk of errors during the implementation process of circular practices; Das et al. (2022) report that companies often do not forecast the environmental impact of their new circular business ideas before implementing them, which can lead to problems such as design bottlenecks and unintended rebound effects.

Das et al. (2023) developed the “Circular Rebound Tool,” which helps companies consider these rebound effects in the early stages of the design process when thinking about new circular business models (models that keep resources in use for longer).

Collaboration with Stakeholders for Systemic Change

Partnerships are established with suppliers, customers, and industry stakeholders to drive systemic change. Lopes et al. (2023) report that consumer motivations to adopt circular behaviors can be used to convert companies’ business models from linear to circular.

Examples of Circular Business Models in Action

Circular Fashion: Revolutionizing the Apparel Industry

The research findings by Coscieme et al. (2022) show that creating successful circular business models in fashion requires more than modifying existing ideas; it involves innovation in three key areas:

- Technical Innovation: New technologies for recycling, remanufacturing, and creating durable materials are essential.

- Social Innovation: Changing consumer behavior towards valuing durable garments, their repair, and reuse is necessary.

- Business Model Innovation: Companies need to develop new ways to design, produce, and sell clothing within a circular system.

The fashion industry, known for its environmental impact, is embracing circularity:

- Patagonia: Their Worn Wear program encourages customers to repair and extend the life of their garments.

- Veja: A sneaker brand that uses recycled materials and organic cotton.

Circular Electronics: Rethinking Product Design and Lifecycles

The electronics industry is transforming to reduce electronic waste:

- Fairphone: Modular smartphones designed for easy repair and upgrade.

Circular Packaging: Minimizing Waste and Maximizing Resource Recovery

Packaging is becoming more circular, reducing landfill waste:

- Loop: A reusable packaging system for household products.

- Ecoveritas: A packaging company that uses recycled and compostable materials.

Circular Food Systems: Reducing Food Waste and Promoting Sustainable Agriculture

Donner et al. (2021) studied 39 cases of business valorization of agricultural waste and by-products, identifying a list of critical success and risk factors, classified into five categories: (1) technical and logistical, (2) economic, financial, and marketing, (3) organizational and spatial, (4) institutional and legal, and (5) environmental, social, and cultural factors; highlighting factors such as innovative conversion technologies, flexible input and output logistics, joint R&D investments, price competitiveness for bio-based products, subsidies, agricultural waste management regulations, and acceptance of biotechnology-based production processes, among others.

The food industry is adopting circularity to address food waste:

- Too Good To Go: An app that connects consumers with surplus food from restaurants and retailers.

- Valorization of Fruit and Vegetable Waste: Donner and De Vries (2023) in their research reviewed circular business models that value losses, waste, and by-products of fruits and vegetables along the value chain; finding that many product and service companies have emerged, mainly driven by concerns over the food waste problem within a broader debate on sustainability and circular bioeconomy.

Conclusion: Embracing Circularity for a Sustainable Future

Circular business models offer a transformative path towards a sustainable future, where resources are valued, waste is minimized, and economic prosperity aligns with environmental stewardship. By adopting circularity, companies can not only reduce their environmental impact but also enhance profitability, innovation, and brand reputation. As the world moves towards a circular economy, those who embrace this paradigm will be at the forefront of a sustainable and prosperous future.

In essence, circular business models aim to keep the value of resources in use for as long as possible, creating a more sustainable and resilient economic system. Adopting the circularity approach will enable your company to be more sustainable and prepared for changes in consumer demand for products based on their “environmental quality.”

References

Awan, U., & Sroufe, R. (2022). Sustainability in the Circular Economy: Insights and Dynamics of Designing Circular Business Models. Applied Sciences, 12(3), 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031521

Baldassarre, B., Calabretta, G. Why Circular Business Models Fail And What To Do About It: A Preliminary Framework And Lessons Learned From A Case In The European Union (Eu). Circ.Econ.Sust. 4, 123–148 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-023-00279-w

Brändström, J., Jazairy, A., & Lindgreen, E. R. Barriers to adopting circular business models: A cross-sectoral analysis. Business Strategy and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3653

Chkareuli, V., Darguashvili, G., Atstaja, D., & Susniene, R. (2024). Assessing the Financial Viability and Sustainability of Circular Business Models in the Wine Industry: A Comparative Analysis to Traditional Linear Business Model—Case of Georgia. Sustainability, 16(7), 2877. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072877

Coscieme, L., Manshoven, S., Gillabel, J., Grossi, F., & Mortensen, L. F. (2022). A framework of circular business models for fashion and textiles: the role of business-model, technical, and social innovation. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 18(1), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2022.2083792

Das, A., Konietzko, J., & Bocken, N. (2022). How do companies measure and forecast environmental impacts when experimenting with circular business models? Sustainable Production and Consumption, 29, 273-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.10.009

Das, A., Konietzko, J., Bocken, N., & Dijk, M. (2023). The Circular Rebound Tool: A tool to move companies towards more sustainable circular business models. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances, 20, 200185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcradv.2023.200185

De Bernardi, P., Bertello, A. and Forliano, C. (2023), “Circularity of food systems: a review and research agenda“, British Food Journal, Vol. 125 No. 3, pp. 1094-1129. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2021-0576

Donner, M., Verniquet, A., Broeze, J., Kayser, K., & De Vries, H. (2021). Critical success and risk factors for circular business models valorising agricultural waste and by-products. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 165, 105236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105236

Donner, M., & De Vries, H. (2023). Novel sustainable and circular business models valorizing fruit and vegetable waste and by-products. Fruit and Vegetable Waste Utilization and Sustainability, 165-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91743-8.00014-9

Geissdoerfer, M., Pieroni, M. P., Pigosso, D. C., & Soufani, K. (2020). Circular business models: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 277, 123741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123741

Geissdoerfer, M., Santa-Maria, T., Kirchherr, J., & Pelzeter, C. (2023). Drivers and barriers for circular business model innovation. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(6), 3814-3832. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3339

Lopes, J.M., Pinho, M. & Gomes, S. Green to gold: consumer circular choices may boost circular business models. Environ Dev Sustain (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03930-6

Mostaghel, R., & Chirumalla, K. (2021). Role of customers in circular business models. Journal of Business Research, 127, 35-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.053

Nußholz, Julia L. K. 2017. “Circular Business Models: Defining a Concept and Framing an Emerging Research Field” Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101810

Salvador, R., Barros, M. V., Luz, L. M. D., Piekarski, C. M., & De Francisco, A. C. (2020). Circular business models: Current aspects that influence implementation and unaddressed subjects. Journal of Cleaner Production, 250, 119555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119555

Straub, L., Hartley, K., Dyakonov, I., Gupta, H., Van Vuuren, D., & Kirchherr, J. (2023). Employee skills for circular business model implementation: A taxonomy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 410, 137027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137027

Susur, E., & Engwall, M. (2022). A transitions framework for circular business models. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 27(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13363

Tuni, A., Gutteridge, F., Ijomah, W. L., & Mirpourian, M. (2024). Risks in circular business models innovation: A cross-industrial case study for composite materials. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(4), 2771-2787. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3618

Vegter, D., Van Hillegersberg, J., & Olthaar, M. (2020). Supply chains in circular business models: Processes and performance objectives. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 162, 105046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105046

Editor and founder of “Innovar o Morir” (‘Innovate or Die’). Milthon holds a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation (UPV) and Market-Oriented Innovation Management (UPCH-Universitat Leipzig). He has practical experience in innovation management, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA) and worked as a consultant on open innovation diagnostics and technology watch. He firmly believes in the power of innovation and creativity as drivers of change and development.